The 15th Amendment, which sought to protect the voting rights of Black men after the Civil War, was adopted into the U.S. Constitution in 1870. Despite the amendment, within a few years numerous discriminatory practices were used to prevent Black citizens from exercising their right to vote, especially in the South. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that legal barriers were outlawed at the state and local levels if they denied any Americans their right to vote under the 15th Amendment.

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Despite the amendment's passage, by the late 1870s dozens of discriminatory practices were used to prevent Black citizens from exercising their right to vote, especially in the South.

In 1867, following the American Civil War and the abolishment of slavery, the Republican-dominated U.S. Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act over the veto of President Andrew Johnson. The act divided the South into five military districts and outlined how new governments based on universal suffrage for men were to be established.

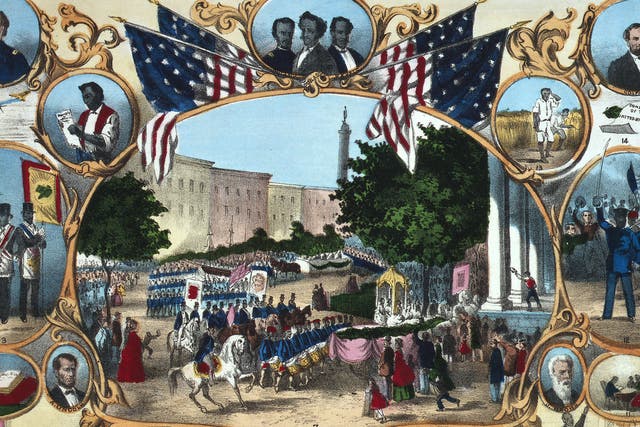

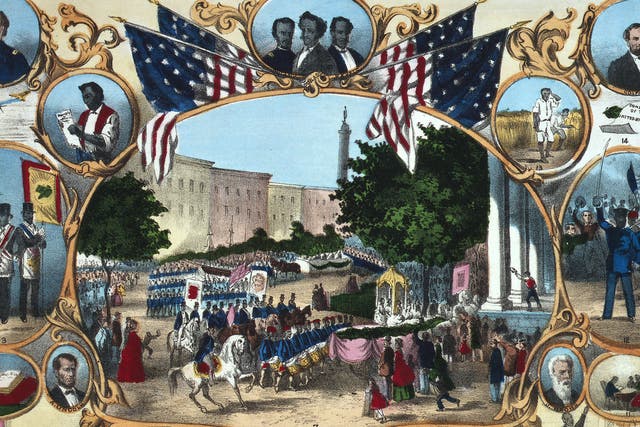

With the adoption of the 15th Amendment in 1870, a politically mobilized Black community joined with white allies in the Southern states to elect the Republican Party to power, which brought about radical changes across the South. By late 1870, all the former Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union, and most were controlled by the Republican Party thanks to the support of Black voters.

In the same year, Hiram Rhodes Revels, a Republican from Natchez, Mississippi, became the first African American to sit in the U.S. Congress when he was elected to the U.S. Senate. Although Black Republicans never obtained political office in proportion to their overwhelming electoral majority, Revels and a dozen other Black men served in Congress during Reconstruction, more than 600 served in state legislatures and many more held local offices.

The 15th Amendment was supposed to guarantee Black men the right to vote, but exercising that right became another challenge.

For a 14‑year period, the U.S. government took steps to try and integrate the nation's newly freed Black population into society.

Since the Constitution was ratified in 1789, hundreds of thousands of bills have been introduced attempting to amend the nation's founding document. But only 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution have been ratified.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965, aimed to overcome all legal barriers at the state and local levels that denied Blacks their right to vote under the 15th Amendment.

The act banned the use of literacy tests, provided for federal oversight of voter registration in areas where less than 50 percent of the non-white population had not registered to vote and authorized the U.S. attorney general to investigate the use of poll taxes in state and local elections.

In 1964, the 24th Amendment made poll taxes illegal in federal elections; poll taxes in state elections were banned in 1966 by the U.S. Supreme Court.

After the passage of the Voting Rights Act, state and local enforcement of the law was weak and often ignored outright, mainly in the South and in areas where the proportion of Black citizens in the population was high and their vote threatened the political status quo.

Still, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave Black American voters the legal means to challenge voting restrictions and vastly improved voter turnout.

The 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution. National Geographic.

15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Primary Documents in American History. Library of Congress.

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.